Tagged: wellbeing

Transition Is A Banquet

Floris van Dyck, circa 1615. Source.

Transition is not a one-way street, or a bowling lane with the bumpers up. Transition is not a recipe with precise measurements, or a fixed curriculum, or a rulebook. Transition is not a set protocol, dictated by faraway experts. It is far too intimate and important for that.

Transition is a banquet. A table overflows with delicious offerings. Bowls of ripe fruit, loaves of fresh bread, the shifting fragrances of herb and spice. Pepper, rosemary, cinnamon, mint.

You are welcomed to this feast as an honored guest. Your cup is filled and the table is set. Take your seat.

There is no right way or wrong way to dine at your own banquet. Let taste move you. You can fill up on bread or skip right to dessert. You can eat nothing but grapes or try a little bit of everything. You can fill your plate once or many times. All is offered to you without question or terms.

Who can judge the tastes you combine? Will you allow anyone to diminish your enjoyment? No–you will savor the smells and the tastes and the textures. You will nourish your body and soul. You will laugh with your friends and you will get seconds as you damn well please. This is far too good for shame or petty limitations.

Transition is an emergency exit; go through it. Transition is a tourniquet; apply it. Stop the bleeding. Cease the flames.

And then stand among ashes in the burned-out room, sunshine streaming through smoke, and the cold rain of the sprinkler system, and the shrill, relentless pulse of the alarm. Put down the fire extinguisher.

The time has come to dance.

Freer & Freer

A pink flamingo, because why not? Source.

As a queer trans man, internalized homophobia intersects with my trans status in complex and painful ways. Being trans put me on the defensive, all the indignities like lighter fluid on the fire of insecure manhood. It’s only now, years past transition, that I feel safe and strong enough to let go.

Accepting that I am bi/queer in terms of orientation has changed my life. I have stopped trying to seem straight–something I had no idea I’d been doing, but which nonetheless severely limited me. Suddenly people are reading me as queer again and it feels really good. I no longer police my body language or my vocal mannerisms. How heavy was the weight of the fear of seeming gay!

[Side note–I am still using the word bi but I’m identifying more and more with just queer. I am realizing that attraction to masculine genderqueer people is a major region of my sexual landscape, which makes “bi” just seem a bit off. While my attraction to men is still feeling kind of vague and confusing, my attraction to genderqueer people feels more fully formed. But I’m cool with either term.]

Wow do I have a lot of internalized homophobia going on. I’m shocked at how deep and how toxic it is. I guess I thought, having gone through so many queer identities, I’d be somehow immune–but of course not. I am now unpacking the special flavor of shame reserved for queer men in our society.

It is such a relief to embrace myself more fully, to be okay with my queer masculinity. I notice people reading me as gay, and people with big question marks over their heads as they try to figure out what letter of the alphabet soup to pin on me. I notice the way I talk differently with different people. I can be a gay boy with a bit of flare or a reliable straight bro–whatever. They’re both me, and neither is. I’m enjoying it.

A key piece of this for me is getting more and more comfortable with my trans body. I’ve recently been exploring sexual pleasure using my front hole. I admit to being a little freaked out just typing that–I have so much shame about that part of my body. Thanks a lot, cissexist, misogynist society.

When I first started exploring my masculinity, I went hardcore stone in the sense of not being touched. This allowed me to engage sexually, which was awesome. As I transitioned and my body changed, I got rid of my dildo and started using my attached dick. But I never started using my front hole, not even by myself, until like two days ago. That part of my body was off limits for about seven years. Seven years is a pretty long time.

Alma and I were talking about my fear and shame around enjoying that part of myself. She encouraged me to put the fear into the format, “I don’t want to _______, because if ________, then ________.” This is an exercise we learned for dealing with jealousy and insecurity around nonmonogamy. (Did I mentioned we’re poly now? We’re poly now. It’s been a fun and eventful summer, haha.) I took a deep breath, quieted my mind, and allowed an answer to unfold. My mind replied,

I don’t want to have sex using my front hole, because if we do that, and I like it, then I will be a faggot.

This thought shocked the hell out of me. Wow, ouch, how horrible. I didn’t even know that idea was in there.

In exposing these contortions to the light, I release them. I get freer and freer. There is no end to freedom.

Queers Do It Better

Queer people seem to be laboring under less sexual shame than cis, straight people. Don’t get me wrong–I know plenty of very cool, sexually liberated cis, straight folks, and some queer people who are completely shut down around sexuality. But in my observation, the trend is stark and striking. The queer people I know just seem more relaxed, uninhibited, embodied, and joyful when it comes to sex and gender. Anyone who’s ever been to a Pride parade probably has some sense of what I mean.

Alma and I have recently been discussing this as a fascinating paradox of our cissexist, heterosexist culture. You’d think it would be the reverse: that since cis, straight people are constantly told their sexuality and gender are legitimate and good, they would be confident and happy and free. And at the same time, since queer people are constantly shamed and berated, especially as we’re growing up, you’d think we would be limping along, loathing ourselves, barely functional.

Yet almost the reverse seems to be true. So many cis, straight men and women are suffocating under extremely narrow ideas of what it means to be a man or woman, what it means to be a lover. So many people feel that if you need or want to discuss your sexual desires with a partner, you have already failed, for you should be able to read minds. So many people feel their bodies are broken and horrible because they don’t fit some absurd standard.

Meanwhile, queer folks, having already broken the mold, seem much more willing and able to figure out what works for us and ask for it. There is far less of a taboo within queer subcultures on stuff like using sex toys, doing kinky stuff, etc. I’m also thinking of trends like gay and lesbian couples having more equitable divisions of housework.

And so, ironically, being shamed and rejected actually offers a special path to freedom. We can never fit the boxes, so oftentimes, we simply quit trying. Gender roles can’t accommodate us, so we figure out what works in each relationship. The heteronormative script can never work for us, so we write our own.

We initially challenge the system as an act of pure survival. But pull one thread and the whole damn tapestry falls apart. Pretty soon we’re challenging the system just for fun.

7 Tips For Surviving Your First Year On T

American lightweight boxer Leach Cross, circa 1910. Source.

So you’ve decided to take testosterone. Starting T is an exhilarating and highly disorienting experience. Along with much anticipated changes like a lower voice and a squarer jaw, you’re bound for a radically altered social landscape and shifting internal world. You’re coping with the demands of a second adolescence and a gender transition–and you’ve probably got a full plate of regular life stuff, too.

My first year on T was one of the most beautiful, transformative, stressful and challenging passages of my life. Nearly five years later, I feel at home in my body and my social role; gender isn’t on my list of concerns. If transition is right for you, and T is part of that transition, some time on testosterone is likely to give you a similar sense of ease, belonging, and the precious freedom to worry about other things. Testosterone therapy works. The trick is getting through the intensity of transition with your resources and relationships intact. Here are a few suggestions for surviving your first year on T.

Each person is different, so please feel free to take or leave anything here as it is helpful to you. I’ve aimed this post at people taking T with the intention of bringing levels into the male range.

1. Expect chaos. You are diving head first into a storm of transformation–physical, social, emotional and otherwise. So expect stormy conditions for awhile. Your sleep, appetite and libido are all likely to change dramatically (including possibly increasing by an order of magnitude). You may also notice that your moods are all over the map and that people are treating you differently. Know that you are going through an intense period of change. Remind yourself that this does not last forever. Make any accommodations that you can to make this a bit easier on yourself. Eat snacks, take naps, take time to care for yourself. This is not good time to take on any huge new projects. Let transition be your project for awhile.

2. Express yourself. This is an emotional time. Hormones are throwing your moods out of whack. You’re undergoing an important process that you may have brooded over for years. And you’re coming up against the longing, shame, stigma, and hope that characterize the trans experience.

I found that, along with some moodiness associated with my body being in flux, starting T brought up a lot of emotions around being trans. For the first time, I was able to feel my anger at my family and my society for failing to see and accept me. Moving through these feelings is an essential part of the transition process.

Make sure you have plenty of opportunities to vent, share, and connect with other people. See a counselor, talk with friends and family, attend a trans support group, play your favorite sport, keep a journal, create music or artwork, yell as loud as you can from the top of a mountain. Whatever strategies work for you, be sure to create space for your feelings and find ways to express them.

3. Patience is a virtue you probably don’t have. After all the agonizing about transition, after all the hoops and hassles, comes another tremendous challenge–more waiting! You have to wait for your voice to drop, wait for hairs to grow, wait for your body to change shape, wait for others to see you as male. Perhaps you are more patient than I, but this was one of the single hardest parts of transition for me. I was tired of waiting and I had an intense fear that testosterone would somehow not work on me and my body would never change.

But it did work, and it does work. A year from now, you are going to look very different. As much as you’re able, enjoy the ride. Be patient if you can be. At least, be patient with you impatience.

4. Masturbate. Everybody talks about how libido increases with T, and for me, it was totally true. If masturbation is something you enjoy, now is an excellent time to enjoy it. I jerked off a lot during my first year on T. It’s a great way to adjust to any libido changes, and also provides a nice chance to relieve stress and get to know your changing body.

5. Be self-absorbed. Might sound like weird advice. But people in transition are guaranteed to be a bit more self-absorbed than usual. It’s an intensely introspective, self-focused process. After years or decades of living in the closet, our selves need some extra attention. Like the first time around, this adolescence is a process of self-expression and discovery. It’s important to pay attention and try on different ways of moving and being. So don’t fight it–just go with the flow and be self-absorbed for awhile. Trust that by going into this process completely, you will soon enough arrive on the other side.

Chemical structure of testosterone cypionate. Source.

Also be prepared to listen to their feedback for you. At some point, someone is going to tell you that you’ve been a jerk recently, you’re angrier than you used to be, or you’re waving your male privilege around. From one guy to another, they are probably right. Don’t make time for folks who put you down or reject your transition–but be ready to hear challenging feedback from the people who love you. This is just part of being a dude in our society; you’re not going to do it gracefully on your very first try. Listen with patience and openness, and be curious about how your behavior can change.

7. Celebrate small changes. Most of us are focused on the big, exciting changes, like muscles, a beard and being seen as male everywhere you go. But the little changes are just as delicious, and in some ways, it’s the small stuff that really makes your transition. Notice the new hairs sprouting up on your belly, each time your voice cracks, the way people move a little differently around you, the veins just a bit more visible on your arms, even the pimples. It’s all these tiny signals that sooner or later come together and present a new side of you to the world. Enjoy them.

Readers–what advice would give to someone just starting T? If you’ve started T recently, how are things going so far?

Shame’s Far Shore

Shame is a small, smooth stone that sinks into our bellies and stays there. Incredibly heavy, impossibly dense, a tiny pebble that can tear down a vast machine. We feel shattering pain, then gnawing numbness, and the beast is at the door again.

Shame is frostbite. Creeping, seeping into flesh, consuming everything. I was so riddled with the sickness, my fingers swelled, darkened, and finally snapped off. Shame could take me apart piece by piece and leave me rotting on the cold and lonely tundra of the heart.

Shame is poison. Evil acid overdose, I writhe and tremble in the grips of that long fever. Cold sweat, stomach sick, snake in the belly. Black bile vomit. Hot stinging tears.

Shame is a whisper, the memory of loneliness. Shame is the half-heard melody spilling from some unseen neighbor’s window, bits of a song I almost think I recognize. Shame is the smell of spilled gasoline in summer, drunken rainbows swirling over asphalt.

Shame is a cavern. Cool and dark, the smell of bats and mineral water. A breeze arises from somewhere deep within the earth, ancient, beckoning. Come closer. I follow the sound of running water. Bioluminescent creatures hide in the hollow places. I see by the green of their starlight.

Shame is not endless. Reach into your belly and pull out the stone. Come in from the cold.

Vomit until no poison remains. Hum an old song to yourself.

Enter the cave.

Hysterical Man: 4 Lessons Learned Preparing For Middle Surgery

I’ve been processing the prospect of a hysterectomy for the past year. I’m at the point where I definitely want the surgery and will probably schedule it as soon as I don’t have a bunch more urgent stuff demanding my attention (i.e. when the semester is over). I have to say it’s been an excruciatingly painful aspect of my transition. A few thoughts on where I’m at and how I got here.

Mules are also sterile, and this one is ready for a nap. I guess there’s just something about being between categories. Photo: David Shankbone.

1. Sterility is a really big deal. When I went in to get a prescription for testosterone, my doctor asked me if I wanted to preserve the possibility of having a biological child. I was like, um, yeah, hell no. I was also 21 years old and way more concerned with paying for beer that night than with being a parent someday.

Letting go of the possibility of having a biological child has been the hardest and most heart-wrenching aspect of this experience. I don’t want to use any of the options available to me for having genetic offspring. There are so many reasons for this, I don’t even want to get into it. Suffice to say that even though I don’t want to use what I’ve got–just the prospect makes me queasy–it’s still hard to let it go. It means letting go of the fantasy that I could ever be a biological father. In confronting this reality, I have felt disappointed, cheated, and humiliated. I have felt left out of the great dance of life, a lonely alien. It feels strange to be so sad, yet so repulsed by the options that are open to me.

2. I am in profound denial about my body. I have never accepted the fact that I was born with a female body. I have to admit that I just straight up do not believe it, to this very day. There’s some pretty solid evidence for my view in that I am, you know, a man. Again I ask, WTF God? WTF?

This is a very deep-seated belief that is beyond all logic and is extremely resistant to change. As far as I can tell, I have always carried the worldview that I am male and it seems I always will. This is the reason approaching hysterectomy has been so painful–it has forced me to experience the cognitive dissonance of being transsexual in a whole new horrible way.

My take on this is, to paraphrase Eckhart Tolle, when you can’t accept, accept your non-acceptance. I accept that I am a trans man, that I have a view of my body as male that is not going to change, and that the thing I can change is my body. I accept that I cannot be a good custodian to female reproductive organs. It’s just not realistic for me at all. So a hysterectomy is something I can do for myself and for my health, out of love.

3. Grieving is necessary. I spent a good while feeling heartbroken about my status as soon-to-be-sterile and never having the option to be a biological father. This was an absolutely essential process for me. It’s normal to grieve over this kind of thing, and we need to allow ourselves the space and time to fully go there.

I can now see that a lot of my grief is about lingering shame and pain around being trans, rather than about parenthood (though of some of it really does have to do with parenthood). I have an ingrained belief that being able to father a child has something to do with being a “real man.” I’m still dealing with this; cultural ideas like that are just hard to shake off.

4. Planning a family is about a lot more than gametes. As I began to see the light at the end of the tunnel of my grief, I got a reality check about my hopes to be a parent. Having a child is something I want to do with my wife, obviously, but it’s only recently that I’ve been able to really consider her feelings. In retrospect, I’ve been pretty myopic and selfish about the whole thing; but at the same time, I really could not have gotten to this point without moving through my grief.

Alma has always wanted to adopt and has absolutely zero interest, or really less than zero interest, in ever being pregnant. I can now enjoy the wonderful match we have in this area and feel good about supporting her in her bodily autonomy.

I’m enjoying my new-found clarity about my own feelings, hopes and fears. I’ve come to realize that I actually do not care about having a biological descendant or sharing that connection with a child. I do care very much about being a father someday and I hope to adopt children with my partner. There is a scary vulnerability in this, as I have no idea if it will work out. But it’s real and it’s honest, a genuine dream.

How has your transition impacted your feelings and choices about fertility and parenthood?

Thanks to Lesboi for teaching me the term “middle surgery” for hysterectomy.

Giving Up, In A Good Way

Massive wall of water, suspended. Narrow space of dry ground, an alley through the sea. I am standing on a ladder in the sand, leaning against the liquid wall. I am frantically laying tiles on the water, one little square at a time, trying to hold it up, reinforce it. I am madly laying the tiles, covering up just a few feet of this massive surface that stretches on for miles. Suddenly, I stop. There is no need for me to cover the water, to build a wall against a wall. God has already parted the sea.

This recent dream pretty much sums up the pickle I’ve been in lately. I am feeling immeasurably better since my last post. I have reoriented myself internally and, though I am just as busy, I am far less stressed out.

I realized that I have been suffering from a severe case of trying too hard. Indeed, trying too hard seems to be at the root of much of my longstanding anxiety. I have a habit of constantly trying: trying to be polite; trying to be good; trying to be perfect. I try at everything. I try hard in school, work, relationships, life. I try hard in my spiritual practice. I try hard, very hard, to relax (what an oxymoron!).

There is a hilarious irony underlying all this, in as much as trying actually undermines both being and doing. This stressed out, effortful trying is an expression of basic fear. It communicates a fundamental lack of trust in the world and in oneself. Far from improving one’s performance or helping one to meet goals, trying diverts energy, corrodes calm, and goes against the flow of life. All in all, trying makes action inferior, cramped, inhibited, uninspired, and it is incompatible with wellbeing.

So I have stopped trying. I am not trying to be a good student, counselor, partner, friend or employee; I am not trying to be healthy, happy, or perfect; I am not trying to relax, be present or meditate.

Quitting trying feels like a great big trust fall in which I am both the one falling and the one catching myself. I feel I am just sitting back and watching the actions of the mysterious intelligence I call myself. With no effort whatsoever, I do all the things I need to do, know all that I need to know, and more than that. Words just come out of my mouth spontaneously, and they’re often very appropriate words; I walk out of my house and directly to my workplace, somehow knowing the way. It’s amazing. And it really underscores just how little good trying does me. It seems I can completely stop trying and, far from my fears of my life crumbling into a twisted mess of pain, the only immediate consequence is that I feel a lot better.

I am still doing. I go about my day; I attend to the tasks that greet me. When tension and anxiety arise I remind myself: I am not trying. I am not trying to do an excellent perfect job at this or that, so if I screw up, if it doesn’t turn out right somehow, what’s the big deal? At the same time, I am not trying to be a super present spiritual person, so if I am worried and preoccupied, who cares? I’m not trying to do or be anything in particular–so whatever I’m doing and being is fine.

Scrambling

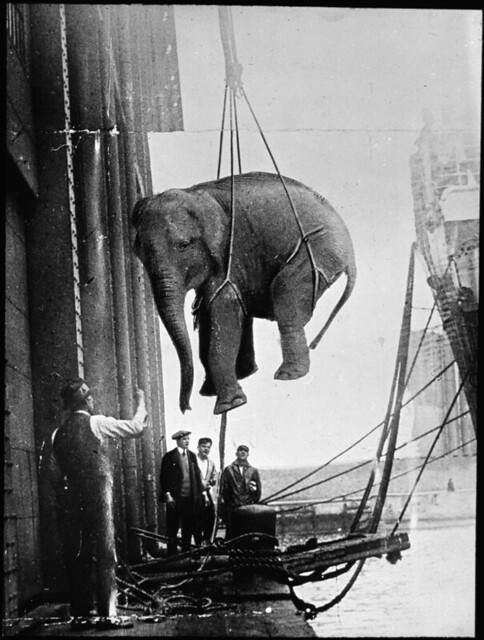

At first I thought I felt like one of the people trying to hoist the elephant, but no. I feel like the elephant. Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums.

I am struggling right now in my other transition–adulthood. I am feeling really overwhelmed. I’ve been stressed out for a while, but I seem to have hit some kind of new threshold. The combination of grad school classes, counseling clients, intensive supervision, my job, joining the board of a professional organization, looking for an internship for next semester with time running out, and, you know, life, trying to be a good partner, son and brother, and all the little tasks that demand doing daily: dogs, chores, shopping, appointments, bills, prescriptions, phone calls… Holy shit, how the hell do people do this?!

Writing it out, at least, I can see why I feel overwhelmed. I really have a lot going on right now. The counseling & supervision is such a challenge in itself. It’s very exciting and rewarding, and I can see growth and change in myself and my clients. But wow, it pushes me so hard, I don’t have that much energy for the zillion other things going on.

I keep getting waves of anxiety, feeling like an imposter. What the hell am I doing? Who am I kidding? I’m terrified.

On the one hand, I feel like, what a joke that I am supposed to be helping others with their mental health–I’m a fucking mess! On the other hand, the nature of the work inspires me to be good to myself, to not work myself too hard, because to make myself miserable helping others be well is just absurd (not to mention impossible).

It is so damn bizarre. I’m like, ok, one minute I’m scrambling to finish a paper; then I’m in a meeting for work; then I’m coaxing someone into a signing a piece of paper promising not to kill themselves; then I’m having dinner with my partner; then I’m giving a presentation on how to help undergraduates write essays; then I’m doing dishes; then I’m listening to someone talk about being raped; then I’m watching a video of myself listening to someone talk about being raped, as another person pauses the video every few minutes to ask, “What were you feeling at this moment?”; then I’m cold-calling agencies and pleading with them to let me work for them for free; then I’m trying to get somewhere on time; then I’m sitting in tiny room with a sobbing man; then I am stopping a moment to smell the first lilacs; and a voice comes through my headphones, saying,

One generation goes, and another generation comes; but the earth remains forever. The sun also rises, and the sun goes down, and hurries to its place where it rises. The wind goes toward the south, and turns around to the north. It turns around continually as it goes, and the wind returns again to its courses. All the rivers run into the sea, yet the sea is not full. To the place where the rivers flow, there they flow again. All things are full of weariness beyond uttering. The eye is not satisfied with seeing, nor the ear filled with hearing. That which has been is that which shall be; and that which has been done is that which shall be done: and there is nothing new under the sun.

Alma and I keep joking that we are babies pretending to be adults. Funny cuz it’s true. I am in over my head.

Against Asking “Male or Female?”

I’ve written before about my evolving relationship with my post-transition body. Last night while meditating naked (don’t knock it til you try it), I found myself staring at my junk, which is pretty typical. And suddenly I wondered, why the staring? What am I looking for? In an instant I realized that I am looking at my penis to confirm that I am a man. I am looking to my body to validate my transition, to prove I really am a guy, like I still need to convince a skeptical mother and bigoted society that my transition is right.

I began to laugh then, because, of course, my dick cannot do that. Of course my genitals don’t determine or validate my gender! Hello, I’m trans, I supposedly know this.

Yet once my body became congruent with my lived sense of self, I reverted to hegemonic thinking and demanded that my dick demonstrate my manhood. This left me scrutinizing my body for proof of maleness and any sign of femaleness. And this, in turn, left me rather uneasy and unhappy, blocking my ability to just be in my body.

Seeing this, I let go completely of asking the question “Male or female?” about my body. There was a sense of space and relief, like the refreshing burst of silence when a constant hum suddenly stops. Maybe for the first time in my life, I was inhabiting my body, naked, without subtly trying to categorize myself as male or female.

I saw much more fully then, like a fog on my glasses clearing away. And oddly enough, my body became more comfortably male to me than ever before. It was a relaxed, natural masculinity, with a violet aura of sacred queerness. I felt I was seeing my body as someone else might see it, just a body without the screen of pain and memory. I sat in an easy confidence, suddenly liberated from a terrible hunger that had been siphoning away my strength. My body is male, yes, and trans too, and above all, human and very ordinary, soft and olive and animal, covered in fuzz, not problematic in any way.

We’ve been taught to pose the question “Male or female?” constantly. It’s a core process of our society, the rigid sorting of life into these two constructed poles. As gender-variant people, we know this, and we see the violence it does. Yet it is all too easy to do the very same thing to ourselves, whatever our identity or transition status. It’s the path of least resistance, a conditioned habit deeply ingrained, a reflex we don’t even know we have. We ask and ask and ask, aching for an answer that will make us feel okay. The messages we get about ourselves hurt so bad, we feel like we need to hear the right answer or we will never be alright.

But the asking itself is the problem. The more we ask, the more we look for a definitive category that confirms our sense of self, the worse we feel, and the farther we get from our bodies, our lives and our truth.

We can only see ourselves when we look with eyes unclouded by judgment. We can only feel ourselves when we sense with hearts unburdened by need. Compulsively categorizing the world in terms of a male/female dichotomy undermines our ability to actually perceive. If we need some insight to navigate the field of gender, there are other questions we can ask.

So as soon as you can, just drop the question. Don’t answer it, don’t even disagree with it. Just let it go, like a dandelion seed on its parachute in the wind.

You’ll be glad you did.

Many Colors

If a single star were missing

The night sky would grieve

If you were someone different

The world would be less

In former lives now forgotten

You were kind and loved mystery

It was in this way you attained

This fine coat of many colors

If God were a bird

It would be this bird

And the Promised Land

Is this land

Look